Beobachtungen:

Reichenbach Odische Lohe

und andere Bücher

1849 Lebenskraft Band 1 Schluss

1850 Lebenskraft Band 2 Resumee

Konzentration des Odlichts konzentration

1850 The Vital Force preface conclusion

1867 odische Lohe lohe

Die Lohe erster Vortrag

1852 Odisch-magnetische Briefe, 1 bis 16, reichenbach-briefe

1854 Der sensitive Mensch und sein Verhalten zum Ode, Stuttgart und Tübingen (1854) /reichenbach 1854/

Berliner Professoren kommen nicht zur Vorführung seiner Experimente:

reichenbach-berlin-professoren

v. Reichenbach weist Strukturen nach beim elektrischen Leiter in dem Strom fließt:

reichenbach-annalen-1861.htm

Bestätigung seiner Versuche in heutiger Zeit:

2012 strom-sehen-002.htm#kapitel-02

2013 bbewegte-materie.htm#kapitel-02-01-06

Aussagen und Bewertung zu v. Reichenbachs Experimenten durch O. Korschelt und einen "ungenannten" Physikers :

korschelt-1892-seite-162-197.htm

|

| Abb. 01: Karl Ludwig

Freiherr von Reichenbach (February 12, 1788 –

January 1869) http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7d/Karl_Reichenbach.jpg/200px-Karl_Reichenbach.jpg |

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_von_Reichenbach

Nach dem Studium der Naturwissenschaften in Tübingen arbeitete er für die Eisenhammerwerke im badischen Hausach. Dort entwickelte und vermarktete er neuartige Öfen für die Holzverkohlung. Nach seiner Promotion siedelte er ins mährische Blansko über, um für den Grafen Salm in dessen Eisenhüttenwerken zu arbeiten. Während dieser Tätigkeit beschäftigte er sich mit den Bestandteilen des Holzteers. Dabei entdeckte von Reichenbach 1830 das Paraffin und 1832 das Kreosot, ein antiseptisches Phenolgemisch. Diese Entdeckungen brachten ihm bald ein beachtliches Vermögen ein und führten 1839 zu seiner Adelung als Freiherren.

Am 15. November 1833 ging in Blansko ein Meteorit nieder. Dieses Ereignis faszinierte von Reichenbach derart, dass er seine Arbeiter tagelang suchen ließ, bis der Meteorit gefunden wurde. In der Folgezeit nutzte er sein Vermögen auch dazu, eine bedeutende Meteoritensammlung anzulegen. Die Begriffe Kamacit, Taenit und Plessit für Bestandteile von Eisenmeteoriten gehen auf ihn zurück. 1869 schenkte er seine Sammlung der mineralogischen Schau- und Lehrsammlung in Tübingen, wo sie heute noch zu besichtigen ist.

1835 erwarb Reichenbach das Schloss Cobenzl bei Wien. Wegen seiner im Schloss durchgeführten Experimente erhielt er von den Wienern den Beinamen „Zauberer vom Cobenzl“.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baron_Reichenbach

"Scientific contributions

Reichenbach conducted original scientific investigations in many areas. The first geological monograph which appeared in Austria was his Geologische Mitteilungen aus Mähren (Vienna, 1834).

His position as the head of the large chemical works, iron furnaces and machine shops upon the great estate of Count Hugo secured to him excellent opportunities for conducting large-scale experimental research. From 1830 to 1834 he investigated complex products of the distillation of organic substances such as coal and wood tar, discovering a number of valuable hydrocarbon compounds including creosote, paraffin, eupione and phenol (antiseptics), pittacal and cidreret (synthetic dyestuffs), picamar (a perfume base), assamar, capnomor, and others. Under the name of eupione, Reichenbach included the mixture of hydrocarbon oils now known as waxy paraffin or coal oils. In his paper describing the substance, first published in the Neues Jahrbuch der Chemie und Physik, B, ii, he dwelt upon the economical importance of this and of its associate paraffins, whenever the methods of separating them cheaply from natural bituminous compounds would be established.

Earth's Magnetism

Reichenbach expanded on the work of previous scientists, such as Galileo Galilei, who believed the Earth's axis was magnetically connected to a universal central force in space, in concluding that Earth's magnetism comes from magnetic iron, which can be found in meteorites. His reasoning was that meteorites and planets are the same, and no matter the size of the meteorite, polar existence can be found in the object. This was deemed conclusive by the scientific community in the 19th century.

Odic Force

In 1839 Von Reichenbach retired from industry and entered upon an investigation of the pathology of the human nervous system. He studied neurasthenia, somnambulism, hysteria and phobia, crediting reports that these conditions were affected by the moon. After interviewing many patients he ruled out many causes and cures, but concluded that such maladies tended to affect people whose sensory faculties were unusually vivid. These he termed "sensitives"

Influenced by the works of Franz Anton Mesmer he hypothesised that the condition could be affected by environmental electromagnetism, but finally his investigations led him to propose a new imponderable force allied to magnetism, which he thought was an emanation from most substances, a kind of "life principle" which permeates and connects all living things. To this vitalist manifestation he gave the name Odic force."

siehe auch /Nahm 2012/

The Sorcerer of

Cobenzl and His Legacy: The Life of Baron Karl Ludwig von

Reichenbach,

His Work and Its

Aftermath.

redaktionell überarbeitet

Th T

ryst rist

c z

blos bloß

giebt gibt

irt iert

ire iere

Blau eingefärbte Textstellen: Beobachtungen

Maßeinheiten:

12 Linien = 1 Zoll (2,5 cm)

12 Zoll = 1 Fuß

odische Lohe

" v. Reichenbach, Akad. Vorträge

Sechs Vorträge gehalten in der kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften in Wien vom 11. Mai bis 20 Juli 1865, in freiem Auszuge und durch Zusätze vervollständigt

von Freiherrn von Reichenbach, Phil. Dr. & a . l. Mr.

Wien 1867

Wilhelm Braumüller, k. k. Hof- und Universitätsbuchhändler. "

auszugsweise

"

Erster Vortrag

Die Lohe.

Geschichte und Vorkommen

In den Jahren 1844 und 1845, also bereits vor zwanzig Jahren sagten mir mehrere hochsensitive Personen, daß sie die leuchtenden Ausströmungen aus ihren Fingerspitzen nicht bloß in der Finsternis der Dunkelkammer, sondern schon am Abend, wenn es noch ziemlich helle sei, deutlich wahrnehmen. Ich schenkte diesen Angaben damals nur wenig Aufmerksamkeit und untersuchte sie nicht näher; ich konnte mir nicht denken, wie man am hellen Abende so schwache Leuchten mit Sicherheit sollte sehen können, wie die odischen es sind. –

Aber das war ein Mißverständnis von meiner Seite, welches sich erst nach zwei Jahrzehnten mir aufklärte. Nicht das Odlicht war es, was hier gesehen wurde, sondern eine Begleiterscheinung. In Berlin war es 1862 der Student Herr Zöller, ein gebildeter Sensitiver und trefflicher Beobachter von einigen zwanzig Jahren, der mich aufs Neue aufmerksam machte, daß er nicht bloß in der Finsternis Leuchtendes, sondern auch bei Tageshelle seinen Fingerspitzen etwas feines, bewegliches, farbloses entströmen sehe. Nun suchte ich andere Hochsensitive dort auf, Herrn Wiedach, Frau Sophie Fritzschen, ihre Tochter Elise, Fräulein Marie Kügler, Frau Elise Marnitz und ihre beiden Kinder, Fräulein Scheibe, Herrn Dürieu, Herrn Kuhn u.a.m. Alle gewahrten bei Tage über den Fingern ein zartes Etwas aufsteigen, ¼ bis 2 Zoll lang,

(Seite -2-)

Sie beschrieben es ganz einstimmig aufwärts strömend, etwas gegen Süden hin geneigt, luftähnlich, lichtlos, und wohin man die Finger auch wenden möchte, ihnen folgend. Nach ihren Schilderungen ist es nicht Rauch, nicht Dunst, nicht Duft, es sieht sich an wie feine Lohe, ähnlich, aber merklich zarter als aufsteigende, erhitzte Luft, wie man sie an jedem geheizten Zimmerofen emporsteigen sehen kann.

In Wien wiederholte ich nun diese Beobachtungen bei zahlreichen Sensitiven, und dies zunächst bei meinen eigenen Hausleuten, die in der größeren Hälfte mehr oder minder reizbar für odische Einwirkungen sind, dann mit Kennern und Freunden der Naturwissenschaften, worunter mir erlaubt worden, auf die Beobachtungen des ausübenden Arztes, Herrn Dr. Bilhuber, des Fabriksherrn zu Atzgersdorf, Herrn J. Fichtner, des Tischlers Josef Ezapek, des jungen Herrn Carl Schelnberger u. a. m. öffentlich Bezug zu nehmen. So sind es dann gegenwärtig an 46 gesunde Personen, zumeist Männer, denen ich die Fragen über den Gegenstand der Lohe vorgelegt und die sie alle gleich und übereinstimmend beantwortet haben.

So ergab sich, daß nicht bloß am Tage, sondern auch bei Lampenschein und Kerzenlicht diese duftähnlichen Lohen von sensitiven Menschen recht gut gesehen werden. Und bald mußte ich erkennen, daß sie bei weitem nicht bloß einen Ausfluß aus den Fingern, sondern auch aus andern Gliedern, zunächst aus den Zehen und allen andern hervorragenden Teilen des lebenden Leibes, selbst aus den Ohrenhöhlen ausmachen, ja daß auch andere organische Gebilde, wie Pflanzen, dann Kristalle und sogar unorganische Substanzen, wie Magnete, endlich auch ganz amorphe Stoffe, wie Metallbarren, Quecksilber, Wasser ec. an der Ausgabe und der Erscheinung der Lohe teilnehmen.

Das hohe wissenschaftliche Interesse, das diese vorläufigen Wahrnehmungen durch die Bedeutung ihres gewichtigen Inhaltes wie durch die Größe ihres Umfanges in Anspruch nehmen, mußte mit Notwendigkeit zu einer aufmerksamern und methodischen Untersuchung hindrängen. Ich unterzog mich ihr mit aller Vorliebe und Ausdauer, und wünsche nun hier ihre Ergebnisse mit Genauigkeit auseinander zu setzen. Dabei darf ich wohl bitten, sie als die ersten Anfänge eines einst wahrscheinlich weitumfassenden Zweiges der Naturwissenschaft aufzunehmen, und die Mängel dieser Incunablen ihrer Jugend zu gute zu halten.

(Seite -3-)

Die erste Frage, um welche es sich hier handelt, muß die des Vorkommens und eine möglichst erschöpfende Aufsuchung der Quellen der Erscheinung sein. An diese wird sich die andere anreihen, ob die Lohe bloß der Materie überhaupt anhänge, oder ob sie von deren Form bedingt werde. Dann muß es sich um ihre Beschaffenheiten und endlich um ihre Beziehungen handeln.

Feste Körper:

Ich beginne damit, mich an kleinere und größere amorphe Körpermassen zu wenden, zunächst an einfache Stoffe. Inmitten deren zeigen die Metalle gleich auf den ersten Anlauf in die Augen fallende Ausströmungen von duftigem, loheartigem Wesen. Wenn über den beiden Enden von Stäbchen Blei 4 Linien, über anderen von Wismut, Kupfer, Zink, Antimon, Zinn, Silber 5 bis 6 Linien hohe Lohen schwebten, so flackerten sie auf Stücken von Eisen, Stahl und Messing, von 5, 12 und 20 Pfunden 50 bis 120 Linien hoch; sie wurden am Kranze eiserner Zimmeröfen, von den Ecken großer Eisen- und Kupferblechtafeln, von 6 Fuß langen eisernen Rundstäben 6 bis 24 Linien, von einem Grobschmiedeambos 48, von einem 10 Fuß langen, 2 Zoll dicken gewalzten Rundeisen 60, von einem 5 Zentner schweren Stück Schmiedeeisen 104, von einer Säule von 10 Zentnern Graugußeisen 228 Linien, also über 1 ½ Fuß hoch gesehen. Ich hatte den schönen antiken kolossalen Hund zu Florenz, Molossus, in Gußeisen vor mein Landhaus gestellt. Er wog bei 15 Zentnern mit der Plinte. Von der Schnauze hauchte er 36 Linien, und von jeder Ohrspitze 27 Linien lange Lohe im Freien aus.

Flüssigkeiten:

Hierauf wurden Flüssigkeiten der Prüfung unterzogen. Mit Quecksilber wurde ein 2 Zoll tiefes Glasgefäß so überfüllt, daß es über dessen Rand noch mit seiner bekannten Wölbung hervorstand. Dies gewährte die Möglichkeit, über das Profil seiner Oberfläche ungehindert hinzuschauen. Es entfaltete einen Lohebesatz von 31 Linien Höhe.

Wasser auf dieselbe Weise in ein 10 Zoll hohes Gefäß gegeben, zeigte über seiner Oberfläche 6 Linien Dunstiges. Von 2 nebeneinander gestellten gleichen Wasserflaschen von 1 Fuß Tiefe wurde die eine leer gelassen, die andere bis an den Rand mit schwacher Wölbung überfüllt und dann bei im Profil betrachtet. Während der Rand der leeren Flasche nur 2 Linien Fransen zeigte, lieferte das Wasser in der angefüllten 8 Linien hohe Lohe.

Essigsäurehydrat auf ähnliche Weise in Anspruch genommen, (Seite -4-) schlug sich mit 6 Linien, Alkohol mit 7 bis 8, Äther mit 6 Linien Lohe.

Zusammengesetztes:

Endlich höhere Zusammensetzungen wie Holz, wurden geprüft an einem klafterlangen buchenen Maßstabe. In der Erdparallele aufgehängt gab er 4 und 6 Linien lange Loheströme an seinen beiden Enden. Eine tannene, 7 Fuß lange, 2 Geviertzolle dicke Stange gab 9 Linien Strömung. Ja Zimmergeräte, wie Kirschholztische, entließen von ihren Ecken 12 bis 16 Linien, ein Schreibtisch an zwei Ecken 16 bis 25 Linien lange Lohe. Der Dachfirst meines Hauses war entlang besetzt mit 108 Linien, eine Schornsteinwölbung, kalt, mit 144 Linien Emanation.

(Seite -6-)

Himmelsrichtung.

Brachte man eine große Kristallensäule in die Richtung des Meridians, den negativen Pol rechtsinnig nach Nord gekehrt, so wuchsen die Ausströmungen beider Pole. Dann stieg die Länge am positiven Pole auf 40, am negativen auf 84, in einem andern Falle von 56 auf 144 Linien, in einem dritten Falle auf 86 und 185 Linien. Selbst wenn die Kristalle widersinnig in den Meridian gebracht wurden, behauptete der negative Pol immer noch den Vorzug der Größe vor dem positiven, wenn auch in verringertem Maße. – Üeberdies waren die Lohen am negativen Pole immer reiner, klarer, zarter, durchsichtiger, am positiven merkbar dumpfer, trüber, gedrängter, dichter.

Vorsicht:

Bei diesen Messungen ist jedoch Vorsicht nicht außer Acht zu lassen, welche die Feinheit des Gegenstandes fordert. Der beobachtende Sensitive muß sich so viel immer möglich von allen äußern Einflüssen frei machen. Zu dem Ende muß er trachten, sich so viel als tunlich ist, inmitten des Zimmers zu halten, überall ziemlich gleichweit entfernt von allen größeren Gegenständen, von größeren Geräten, Öfen und Zimmerwänden, von Lustern und Metallapparaten sich stellen; Niemand solle ihm nach stehen; mit dem Antlitz soll er gegen Nord gekehrt sein; die Beobachtung sollen Vormittags vorgenommen werden, nach einem möglichst frugalen Frühstücke; vor allem aber darf der Beobachter nicht zuvor im Sonnenscheine verweilt haben. Sollen polare Gegenstände beobachtet werden, so ist das Anfassen mit den Händen der Richtigkeit der Erfolge immer sehr nachteilig; am Besten tut man, an der Zimmerdecke eine leichte, wollenen Schnürung zu befestigen, und in diese die polaren Gegenstände in Balance zu legen, mit denen man arbeiten will. Wenn man nicht gerade beabsichtigt, ihre Verhältnisse zum Erdmagnetismus kennen zu lernen, so muß man sie in der Parallel halten, und dann das Mittel von zwei Beobachtungen nehmen, von denen jeder Pol in östlicher und westlicher Richtung sich befand.

Bei der Beschauung der genannten Erscheinung muß sich der Beobachter so stellen, daß er den Gegenstand gegen einen dunklen (Seite -7- ) Hintergrund ins Auge bekömmt; er darf ihm dabei nicht allzunahe stehen, die Größe der Entfernung muß Jeder seiner Sehweite anpassen; mancher sieht am besten auf eine ganze Klafter Abstand, wobei das Zimmer nicht allzuhelle beleuchtet und ohne unmittelbaren Sonnenschein sein soll. Man darf die Lohe auch nicht zu lange fixieren, sondern muß dem Auge bald auf diesem bald jenem andern Gegenstande Erholung im Wechsel verschaffen. Endlich ist das Sehvermögen der Sensitiven in beiden Augen nicht gleich. Ich fand dies um mehr als das doppelte verschieden. Ein Bergkristall wurde mit einem linken Auge am positiven Pole 15, am negativen 40 Linien hoch beloht gesehen; gleichzeitig zeigte das rechte Auge nur 6 und 18 Linien Höhe, während beide Augen vereint 36 und 84 Linien Lohe gewahrten. Die Augen verhalten sich also zu den Lohen nicht bloß passiv sehend, sondern sie greifen vermöge ihres eigenen sensitiven Dualismus in die Erzeugung des Bildes auf der Netzhaut aktiv mit ein.

Magnet:

Von hier leitet uns die Untersuchung zur Lohe der Magnete, ebenso sichtbar am Tage wie bei Dämmerung und Feuerlicht. Ein kräftiger Stabmagnet frei in die Parallel gebracht, duftete an beiden Enden Lohe aus, in eben der Weise wie die Kristalle es tun. Dies tat eine kleine Compaßnadel so gut als mehrere Schuh lange Stahlstäbe. Ein zweischühiger Stabmagnet mit einem Quadratzoll Querschnitt, rechtsinnig in den Meridian gebracht, lieferte am positiven genSüdpole 30, am negativen genNorpole 12 Linien lange Lohen. Einem 5 Fuß langen Stabmagnete in gleicher Lagerung entströmten am negativen Ende 23, am positiven 48 Linien Lohe; widersinnig im Meridian liegend am negativen Ende 40, am positiven 18 Linien.

Seite -10-

Schall

Der Schall ist eine ausgiebige Lohequelle. Schon eine einfache Stimmgabel, angeschlagen, hülle sich in eine feine duftige Wolke. – Die Saiten eines Fortepiano, in welches nach niedergelassener Dämpfung stark hineingerufen wurde, gaben 1 Linie hohe Lohe; wenn aber viele Saiten schnell nacheinander und rasch wiederholt angeschlagen wurden, so stieg sie auf 6 Linien über die ganze Besaitung.- Eine umgekehrte Metallglocke von 10 Zoll Durchmesser mit einem harten Holzhammer angeschlagen, besetzte sich rund um ihren Rand mit Fransen von 42 Linien hoher Lohe. Die Strömung war auf der Seite gegen Nord etwas höher als auf dem übrigen Umfange, also auf der mehr negativen Seite ihres Umfanges.

Zweiter Vortrag

Über die Beschaffenheit der Lohe

Seite -25-

Luftbewegung

Die Bewegung der Luft ist nicht ohne Einfluß auf die Lohe. Blies man darein, so wich sie einen Augenblick wie eine gutbrennende Flamme, wie brennender Alkohol zurück, stellte sich aber im Augenblicke wieder her. Richtete man einen Blasbalg darauf, so wich sie etwas nach der Hinterseite des lohausgebenden Körpers, ohne zu verschwinden, und nahm im nämlichen Augenblicke ihre vorige Stellung wieder ein, so wie der Windzug nachließ. "

|

| Abb. 02: Titel des

Buches von Reichenbach. Die odische Lohe 1867 |

|

| Abb. 02a: Titelblatt des Buches von

v. Reichenbach 1849 books.google.de/books?id=MkkyAQAAMAAJ |

|

| Abb. 03: Übersetzung

seines Buches 1850 "Lebenskraft" --> "The

Vital Force" . books.google.de/books?id=KukRAAAAYAAJ Ab Seite Seite 243 im achten Kapitel schreibt Reichenbach über Od und Magnete: The odylic luminous phenomena seen over the magnet |

|

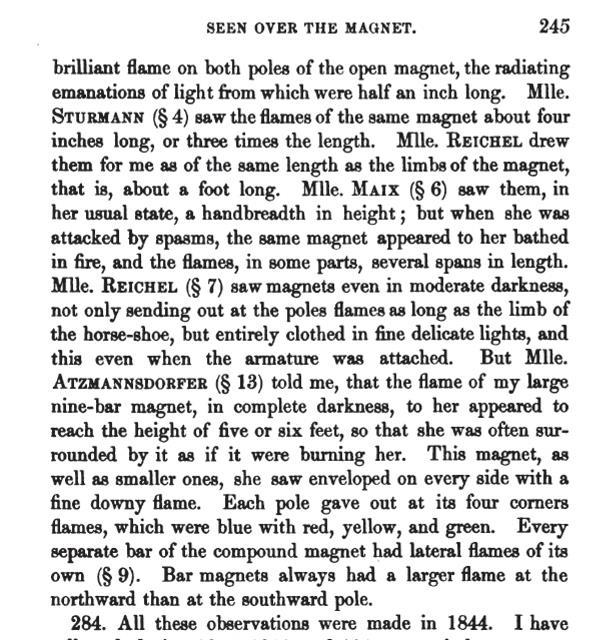

| Abb. 04: Auszug aus

dem Buch von 1850, Auswirkungen von Magnetfeldern

können für Sensitive "sichtbar" sein. "Still earlier she had seen a glowing thread of light along the edges of the magnet, and a week before she had seen a beautiful" ... 245.. weiter siehe Abbildung Übersetzung (FB): Etwas früher hat sie einen glühenden Lichtfaden entlang der Kanten eines Magneten gesehen und eine Woche vorher hat sie gesehen eine wunderschöne..... Seite 245 ..... strahlende Flamme an beiden Polen des offenen Magneten, die strahlenden Licht-Aussendungen mit einer Länge von einem halben Zoll (12 mm). Fräulein Sturmann (§4) sah die Flammen des gleichen Magneten ungefähr 4 Zoll (10 cm) lang oder dreimal die Länge. Fräulein Reichel zeichnete sie für mich mit der gleichen Länge wie die Polschuhe des Magneten, d.h. einen Fuß (30 cm) lang. Fräulein Maix (§6) sah sie in ihrem Normalzustand eine Handbreit hoch; aber wenn sie an Spasmen-Attacken litt, dann erschien derselbe Magnet, als wenn er in Feuer baden würde und die Flammen an einigen Stellen einige Spannen (Handbreite) lang wären. Fräulein Reichel (§7) sah Magnete sogar in halb abgedunkelten Räumen, und zwar nicht nur, daß sie an ihren Polen Flammen aussandten wie der Bogen eines Hufeisens, sondern ganz eingedeckt waren mit feinen zierlichen Lichtern und selbst dann, wenn die Armatur befestigt war. Aber Fräulein Atzmannsdorfer (§13) erzählte mir, daß die Flamme meines großen Magneten aus neun Stäben ihr in voller Dunkelheit erschien bis zu einer Höhe von fünf bis sechs Fuß (1,5 bis 1,8 m), so daß sie von ihr umgeben war, als würde er sie anbrennen. Diesen Magnet, genauso wie kleinere, sah sie umgeben auf jeder Seite mit kleinen flaumbärtigen Flammen. Aus jedem der Pole kamen jeweils aus seinen vier Kanten Flammen, die blau mit rot, gelb und grün waren. Jeder einzelne Stab eines Verbundmagneten hatte seitlich eigene Flammen. Stabmagnete haben immer eine größere Flamme am Nordpol als am Südpol. 284. Alle diese Beobachtungen stammen aus dem Jahr 1844. |

Zur Bezeichnung der Pole eines Magnetfeldes, Vergleich mit einer Kompaßnadel

Reichenbach verwendet "genNorden" und "genSüden"

Reichenbach--Dynamide, Band I,

"§225 ... In der Regel sprach sich der genNordpol, also das negative Ende der Nadel, kühl, der genSüdpol, die positive Kehrseite derselben, warm aus."

Im Norden der Erde ist der magnetische Südpol, im Süden der magnetische Nordpol.

Die Bezeichnung aus heutiger Sicht: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nordpol

"Ursprünglich wurde dasjenige Ende einer Magnetitnadel, das in Richtung geographischer Norden zeigte, Nordpol der Nadel genannt. Damals hatte man noch keine Kenntnis von dem dahinter liegenden Mechanismus. Erst sehr viel später wurde man sich dessen bewusst, dass diese von der Physik übernommene Benennung dazu führte, dass die Erde verwirrenderweise in Richtung des geographischen Nordpols physikalisch gesehen einen magnetischen Südpol hat, und in Richtung geographischer Südpol den magnetischen Nordpol. Die Stelle an der Erdoberfläche, wo die Feldlinien des physikalisch magnetischen Südpols der Erde senkrecht austreten, wird zudem geographisch ebenfalls als magnetischer Nordpol bezeichnet. Dies liegt daran, dass es um den Nordpol geht, der sich durch das Erdmagnetfeld ergibt, nicht um die physikalische Polarität des Pols.

Um Missverständnisse zu vermeiden, könnten die Begriffe „Arktischer Magnetpol“ und „Antarktischer Magnetpol“ verwendet werden, was zwar auch angesichts der Polaritätswechsel über geologische Zeiträume hinweg eindeutiger wäre, aber praktisch ungebräuchlich ist. In der Regel wird mit „magnetischer Nordpol“ in einem geographischen Zusammenhang immer der magnetische Pol nahe dem geographischen Nordpol bezeichnet."

Zusammenfassung

K. v. Reichenbach

Physikalisch-physiologische Untersuchungen über die Dynamide des Magnetismus, der Elektrizität,

der Wärme, des Lichtes, der Kristallisation, des Chemismus in ihren Beziehungen zur Lebenskraft“,

Braunschweig (1850), 2. Aufl. in Band I,

Reichenbach--Dynamide, Band I, Seite 209 — 218 *** abgedruckt auch in /Korschelt 1892/ Seite 140 bis 157

im Anschluß an §276

"Schluss.

Fasse ich alle in den vorstehenden sieben Abhandlungen auseinandergesetzten Versuche und Beobachtungen mit den daraus gezogenen Folgerungen nahe zusammen, so ergeben sich folgende Sätze für Physik und Physiologie :

1. Die tausendjährige Beobachtung, dass der Magnet auf den menschlichen Organismus fühlbar reagiere, ist weder „Lug, noch Trug, noch Aberglauben", wie viele Naturkundige heutzutage irrtümlich vermeinen und ausgeben, sondern eine wohlbegründete Tatsache, ein lautes physikalisch-physiologisches Gesetz in der Natur.

2. Von der Richtigkeit und Genauigkeit dessen sich zu überzeugen, ist eine ziemlich leichte, überall ausführbare Sache; denn überall gibt es Leute, deren Schlaf durch den Mond mehr oder weniger beunruhigt wird, oder die an nervösen Verstimmungen leiden; fast alle diese empfinden stark genug die eigentümlichen Reizwirkungen des Magnete, wenn er streichend vom Kopf über ihren Leib herabgeführt wird. Zahlreicher noch finden sich gesunde und rüstige Menschen allenthalben, welche den Magnet ganz lebhaft empfinden; viele fühlen ihn schwächer; manche erkennen ihn noch leise; die grosse Menge endlich nimmt ihn gar nicht, mehr wahr. Alle diejenigen, welche diese Reaktion erkennen, und deren Anzahl den dritten oder vierten Teil der Menschheit auszumachen scheint, werden hier mit dem gemeinschaftlichen Ausdrucke „Sensitive" bezeichnet. §60

3. Die Wahrnehmungen jener Einwirkung drängen sich hauptsächlich den beiden Sinnen des Gefühls und des Gesichts auf, des Gefühls, durch eine Empfindung von scheinbarer (§217) Kühle und Lauwärme (§225); des Gesichts, durch Lichterscheinungen bei lange anhaltendem Aufenthalt in tiefer Dunkelheit, welche von den Polen und Seiten der Magnete ausströmen. §8, 9, 15

4. Die Fähigkeit, solche Wirksamkeit auszuüben, kommt nicht bloß dem Stahlmagnete, wie wir ihn aus unseren Werkstätten hervorgehen sehen, oder dem natürlichen Magneteisensteine zu, sondern die Natur gewährt sie noch in einer unendlich mannigfaltigen Zahl von Fällen. — Zunächst ist es der gesamte Erdball, welcher mittelst des Erdmagnetismus auf sensitive Menschen stärker oder schwächer einwirkt. §60 usw.

5. Dann ist es der Mond, welcher mittelst ganz derselben Kräfte gegen die Erde und sofort gegen die Sensitiven reagiert. §118

6. Es sind ferner alle Kristalle, natürliche und künstlich erzeugte, und zwar in der Richtung ihrer Achsen. §31, 33, 35, 50, 55

7. Ebenso ist es die Wärme; §121

8. Die Reibung; §127

9. Die Elektrizität; §159

10. Das Licht; §13f

11. Die Strahlen der Sonne und der Gestirne; §97, 208

12. Insbesondere der Chemismus; §137, 142

13. Dann auch die organische Lebenstätigkeit, sowohl a. der Pflanzen, §25 — als auch b. der Tiere, namentlich des Menschen. §79

14. Endlich die gesamte Körperwelt. §174, 213

15. Die Ursache dieser Erscheinungen ist eine eigentümliche Kraft in der Natur, welche das ganze Weltall umspannt (§213, 214), verschieden von allen bis jetzt bekannten Kräften, hier mit dem Worte „Od" bezeichnet. §215

16. Sie ist wesentlich verschieden von dem, was wir bis jetzt mit dem Worte „Magnetismus" bezeichneten (§42), denn sie zieht nicht Eisen (§37), noch Magnet; (§24, 38) ihre Träger werden vom Erdmagnetismus (§42) nicht gerichtet; sie richten auch keine schwebende Magnetnadel (§38); sie werden von einem benachbarten elektrischen Strome in der Schwebe nicht beunruhigt (§39), und induzieren in Metalldrähten keinen galvanischen Strom. §40

17. Sie tritt, obgleich verschieden von dem, was wir bis jetzt Magnetismus nannten, überall auf, wo Magnetismus erscheint. §43

18. Umgekehrt aber tritt der Magnetismus bei weitem nicht überall auf, wo das Od erscheint; diese Kraft hat also vom Magnetismus unabhängigen eigenen Bestand; der Magnetismus dagegen ist immer an die Gemeinschaft mit Od gebunden. §43, 44

19. Die odische Kraft besitzt Polarität. An beiden Polen des Magnets tritt sie mit konstant verschiedenen Eigenschaften auf: — am genNordpol (§225 Anmerkung) erzeugt sie auf das Gefühl bei herablaufendem Striche in der Kehle eine Empfindung von Kühle (§236) und in der Finsternis eine blaue und blaugraue Leuchte; am genSüdpol dagegen eine Empfindung wie Lauwärme (§225) und eine rote, rotgelbe und rotgraue Leuchte. Ersteres ist mit entschiedenem Wohlbehagen, letzteres mit Missbehagen und bangen Peinlichkeiten verbunden. — Nächst den Magneten sind es die Kristalle (§ 32, 50, 55, 220, 221) und die lebenden organisierten Wesen (§84 bis 89, 253), an welchen sich odische Polarität deutlich zu erkennen gibt. (original: genNordpol, genSüdpol)

20. An den Kristallen sind es die Pole der Achsen, an denen die Odpole sich befinden (§32); an mehrachsigen Kristallen sind auch mehrere odische Achsen von ungleicher Stärke.

21. An Pflanzen ist im allgemeinen der aufsteigende Stock dem absteigenden Stocke odpolar entgegengesetzt; es finden sich aber noch unzählige untergeordnete Polaritäten in allen einzelnen Organen. §248 usw.

22. An Tieren, wenigstens an Menschen, steht die ganze linke Seite in odischem Gegensätze gegen die ganze rechte (§226). Zu Polen konzentriert tritt die Kraft in den Extremitäten, den Händen und Fingern (§254), dann in den beiden Füssen (§23) auf, in ersteren stärker, in letzteren schwächer. Innerhalb dieser allgemeinen Polaritäten finden sich aber unzählige kleinere untergeordnete Sonderpolaritäten der einzelnen Organe gegen einander und in sich. (254) -- Männer und Weiber sind qualitativ odisch nicht verschieden. §227

23. Am Erdball ist der Nordpol für magnetopositiv, der Südpol für negativ angenommen worden; in Folge dessen der gen Nordpol der schwebenden Nadel für negativ, ihr gen Südpol für positiv. In Übereinstimmung damit habe ich den Südpol, der mit dem negativen Magnetpole geht, ebenfalls für negativ „odnegativ" = -Od; den anderen, entgegengesetzten für „odpositiv'' +Od genommen (§231). An Kristallen zeigte sich demzufolge der kalten Abstrich gebende Pol odnegativ, der lauen gebende odpositiv (§231). — An Pflanzen ergab sich im Allgemeinen die Wurzel odpositiv, der Stamm und seine Spitzen odnegativ (§252). — Am Menschen wirkt die linke Seite, ihre Hand und Fingerspitzen lau, widrig und rotleuchtend, folglich odpositiv; die rechte Seite, Hand und Fingerspitzen kühl, angenehm und blauleuchtend, also odnegativ (§226, 231). Bei allen Tieren wird es nicht anders sein. §253

24. Im unmittelbaren Sonnenlichte zeigt sich der rote Strahl und darunter odpositiv; der blaue und darüber, also der sogenannte chemische Strahl odnegativ, das Spektrum also odisch polarisiert. §116

25. Amorphe Körper ohne kristallische Richtung ihrer integrierenden Bestandteile zeigen einzeln keine Polarität; indem aber jeder einzelne in seiner Grenze odlau oder odkühl aufs Gefühl wirkt, und diese Reaktion bei verschiedenen Stoffen verschiedene Grade der Intensität zeigt, so reihen sie sich hernach aneinander und bilden eine fortlaufende Kette von Übergängen in derselben Weise, wie sie ihrer elektrischen Natur nach eine Reihe bilden, die man die; „elektrochemische" nennt. Ganz in derselben Weise fügen sich die sämmtlichen einfachen Körper in eine odische Reihe, die an dem einen Ende die am stärksten positiv odpolaren Körper hat, Kalium usw., am anderen die am stärksten negativen, wie Sauerstoff usw. Und da diese natürliche Gruppierung mit der elektrochemischen nahezu zusammenzufallen scheint, so kann man sie die odchemische Reihe nennen. §236

26. Die Erwärmung (§122, 245) und die Reibung (§129) zeigen +Od; die Erkühlung (§123) und Feuerlicht (§131, 240, 244) -Od. Chemische Aktion wechselt ihren odischen Wert nach Beschaffenheit der in die Tätigkeit eingetretenen Stoffe. (§139, 142, 247) Doch zeigte sie sich bei weitem der grossen Mehrzahl der Fälle nach bisher odnegativ.

27. Von den Gestirnen zeigen sich die, welche ohne eigenes Licht sind, wie der Mond und die Planeten, der Hauptwirkung nach odpositiv (§119, 208, 239); jene, welche Selbstleuchter sind, wie die Sonne und die Fixsterne, der Hauptwirkung nach odnegativ (§100, 208, 239). Das Spektrum derselben zeigt sich aber wieder für sich polarisiert. §116

28. Die odische Kraft, lässt sich an den Körpern fortleiten; alle festen und flüssigen Körper leiten Od auf bis jetzt ungemessene Entfernungen. Nicht nur Metalle, sondern auch Gläser, Harze, Seide, Wasser sind vollkommen gute Odleiter (§47, 81, 113, 118, 121, 141, 167, 203). In etwas geringerem Grade leiten nur weniger zusammenhängende Körper, wie trockenes Holz, Papier, Baumwollenzeuge, Wolle u. dgl. Es findet also einiger, jedoch nur schwacher Übergangswiderstand von einem Körper auf den anderen statt. §47

29. Die Leitung von Od bewerkstelligt sich viel langsamer als die von Elektrizität, aber viel schneller, als die Wärme; an einem langen Drahte hin vermag ein Mensch ihr beinahe zu folgen, wenn er sich beeilt.

30. Das Od lässt sich verladen, von einem Körper auf den andern bringen, oder wenigstens: ein Körper, an welchem freie Äusserung von Od statt hat, vermag einen anderen in ähnlichen odisch erregten Zustand zu versetzen. §29, 45, 72, 82, 105, 118, 143, 198, 202

31. Die Verladung wird durch Berührung bewirkt. Aber auch blosse Annäherung ohne wirkliche Berührung reicht schon dazu hin, doch mit schwächerer Wirkung. §202

32. Die Verladung vollzieht sich nicht so sehr schnell, sondern bedarf zu ihrer Erfüllung einiger Zeit, mehrerer Minuten. §48

33. Weder bei der Leitung, noch bei der Verladung zeigt sich Polarität in der Aufstellung des Ods in den Körpern; diese scheint vielmehr ein Angebinde gewisser Molekularanordnung der Materie zu sein.

34. Die Andauer des odischen Zustandes der Körper nach vollbrachter Ladung und Entfernung von dem ladenden Gegenstande ist nur kurz, verschieden nach Beschaffenheit der Materie, für gesunde kräftige Sensitive selten über einige Minuten erkennbar (§82, 167, 169), für kranke Hochsensitive bisweilen noch nach einigen Stunden fühlbar, z.B. magnetetes Wasser. Die Körper besitzen also einige Koerzitivkraft für das Od. §46, 83, 112, 205

35. Die Körper, welche durch Zuleitung und Ladung geodet worden sind, z.B. Metalldrähte, liefern an ihren entgegengesetzten Enden fühlbare herausdringende Odströmungen, lau oder kühl, positiv oder negativ, wie die Pole, von denen sie ausgingen. §107, 114, 119

36. Das Od teilt mit der Wärme die Eigenschaft zweier verschiedenen Zustände: den eines trägen, an den Körpern fort und durch sie langsam hindurch ziehenden, und den eines strahlenden (§193, 254). In letzterem Zustande wird das Od von Magneten, Kristallen, menschlichen Leibern (§254) und Händen augenblicklich und ohne allen merkbaren Zeitverbrauch auf die Entfernung einer ganzen Zimmerreihe von gesunden Sensitiven empfunden. Alle Vorgänge, welche träges Od über die Körper nur langsam ausbreiten, strahlen es gleichzeitig nach allen Richtungen aus, doch mit verschiedener Stärke; so die Reibung, die Elektrizität, die Wärme, der chemische Process, die gesamten Körper (§201). Die Odstrahlen durchdringen Kleider, Betten, Bretter, Mauern (§23 Anmerkung), jedoch merkbar weniger leicht und behend, als der Magnetismus dies tut, und mit einer gewissen Langsamkeit. Die Durchleitung und Vorladung mittelst blosser Annäherung der Magnet- und Kristallpole, der Hände, amorpher Körper von hoch-odpolarer Stellung usw. scheint sämmtlich auf Odstrahlung zu beruhen, wohin denn auch das sogenannte Magnetisieren empfindlicher Menschen gehört.

37. Elektrische Ströme, durch Sensitive durchgeleitet, bringen keine bemerkbare odische Erregung hervor, noch wirken sie überhaupt unmittelbar auf jene fühlbar anders ein, als auf alle anderen Menschen (§160); mittelbar dagegen, indem sie in anderen Körpern odische Bewegungen hervorbringen, desto stärker (§167. In den elektrischen Wirkungskreis gebrachte Metalle zeigen die lebhaftesten Oderscheinungen. §168

38. Das Licht, welches odisch erregte Körper aussenden, ist überaus schwach, und wohl schon dieser Schwäche wegen nicht jedem Auge sichtbar. Menschen, die nicht stark sensitiv sind, müssen über eine ganze, wohl auch zwei Stunden lang in absoluter Finsternis verweilt haben, ehe ihr Auge hinlänglich vorbereitet ist, um für die Wahrnehmung des Odlichtes geeignet zu sein, während dieser ganzen Zeit darf nicht eine Spur anderen Lichtes sie getroffen haben. Die Ursache hiervon kann jedoch nicht in einer besonderen Schärfe des Auges allein liegen, weil Alle, welche Odlicht sehen, ohne Ausnahme auch mit der eigentümlichen Reizbarkeit begabt sind, die odischen Eindrücke durchs Gefühl wahrzunehmen, sie nach scheinbarer Lauwärme oder Kühle, nach angenehmen oder widrigen Empfindungen zu unterscheiden, die keinem Wandel unterworfen sind. Da diese verschiedenen Fähigkeiten in bestimmten Personen immer gleichzeitig vorhanden, oder alle gleichzeitig abwesend sind, so müssen sie als verbunden betrachtet werden und scheinen von einer eigentümlichen Disposition des ganzen Nervensystems herzurühren, die wir nicht kennen, nicht aber von einer besondern Beschaffenheit einzelner Sinneswerkzeuge.

39. Das Odlicht der amorphen Körper ist eine Art von schwachem äusseren und inneren Erglühen anscheinend durch die ganze Masse hindurch, ähnlich der Phosphoreszenz und mit ihr vielleicht auf einerlei Grundlage ruhend; ein feiner leuchtender Schleier, wie zarte, flaumige Flamme, umhüllt sie. Bei verschiedenen Körpern tritt dieses Licht in verschiedenen Farben auf, blau, rot, gelb, grün, purpurn, meistens weiss und grau. Einfache Körper, namentlich Metalle, leuchten am hellsten; zusammengesetzte wie Oxyde, Sulfide, Jodide, Kohlenwasserstoffe, Silicate, Salze aller Art, Gläser, ja die Mauern der Zimmerwände, alles leuchtet. §206

40. Wo das Odlicht polarisch auftritt, wie im Magnete (§3, 6) und in den Kristallen (§55), bildet es einen von den Polen ausgehenden, flammenartigen Strom, der in der Sichtung der Magnetarme und Kristallachsen fast gradlinig fortgeht, und mit der Entfernung vom Pole sich etwas erweitert, während er an Lichtintensität abnimmt. Er ist bunt in allen Regenbogenfarben (§9, 13), bleibt jedoch am positiven Pole vorherrschend rot, am negativen vorherrschend blau. Nebenbei bleiben Magnete, Kristalle, Hände, ähnlich den amorphen Körpern, durch ihre Masse hindurch leuchtend, odglühend, und ebenso mit einem feinen, leuchtenden dunstigen, Schleier allenthalben umfangen. §8

41. Die Menschen leuchten fast überall auf ihrer Leibesoberfläche, vorzüglich aber an den Händen (§92), dem Handteller, den Fingerspitzen (§93), den Augen, verschiedenen Stellen am Kopfe, der Magengrube, den Fusszehen und an anderen Orten. Von allen Fingerspitzen aus, in gerader Richtung der verlängerten Finger, strömen flammenähnliche Lichtergüsse von verhältnissmässig grosser Intensität.

42. Die Elektrizität, selbst schon die blosse elektrische Atmosphäre, erzeugt und verstärkt in hohem Grade die odischen Lichterscheinungen (§167), jedoch nicht augenblicklich, sondern nach einer kleinen Pause von ein paar Minuten. §169

43. Der Elektromagnet verhält sich wie gemeiner Magnet in Beziehung auf odische Lichtemanationen (§12), und in eben dem Masse, in welchem er magnetischer Steigerung fähig ist, ist er gleichzeitig zur Verstärkung der Lichterscheinungen geeignet.

44. Sonnenstrahlen und Mondschein erzeugen auf allen Körpern, auf welche sie fallen, Odladung, welche an Drähten in's Finstere geleitet, an deren Spitzen Odflammen geben. §114, 119

45. Wärme (§125), Reibung (§129), Feuerlicht (§134, 147, 240) bringen an ins Finstere geleiteten Drähten und ihren Spitzen sichtbare Leuchten hervor, eine Flamme ähnlich einem Kerzenlichte.

40. Jede chemische Aktion, wenn es auch nur einfache Lösungen in Wasser oder Ersätze von Kristallisationswasser bei verwitterten Salzen sind, bewirken an darein eingesetzten Drähten ganz dasselbe in starkem Masse (§146). Aber auch für sich strömen Zersetzungsprozesse Odflamme aus und verbreiten Odglut. $145

47. Der positive Pol gibt die kleinere, aber leuchtendere; der negative die grössere, aber lichtärmere Flamme; erstere, weil gelb und rot, letztere, weil blau und grau.

48. Die Odflamme strahlt Licht von sich aus, das andere Körper in der Nähe beleuchtet. Es lässt sich in Glaslinsen sammeln und in einem Brennpunkte vereinigen (§18). Man muss also die leuchtenden Odemanationen der Körper und ihrer Pole überhaupt bestimmt unterscheiden von Odlicht im engeren und eigentlichen Sinne

des Wortes.

49. Jede Odflamme lässt sich durch Luftbewegung fächeln, durch Hineinblasen hin und her beugen, verwehen und zersplittern §20); an festen Körpern anstossend, biegt sie sich um, folgt ihrer Oberfläche und strömt daran hin, wie jede gewöhnliche Feuerflamme (§20); sie ist sichtlich ganz materieller Beschaffenheit.

50. Man kann ihr jede beliebige Richtung geben, nach oben, nach unten, nach allen Seiten, sie ist also, bis auf einen gewissen Grad, unabhängig von den Einflüssen des Erdmagnetismus. §20, 53

51. Die odischen Lichtausströmungen suchen Kanten, Ecken und Spitzen (§3) und finden an denselben der Elektrizität ähnlich, leichteren Ausgang, übereinstimmend mit dem bei der Leitung beobachteten Übergangswiderstande: an jenen sprechen daher immer die Temperaturdifferenzen und die Lichterscheinungen vorzugsweise stark sich aus. §114

52. Die an ungleichnamigen Polen ausströmenden Odflammen zeigen kein Bestreben, sich mit einander zu verbinden; es findet durchaus keine merkbare gegenseitige Anziehung statt, und somit auch hierin gänzliche Verschiedenheit vom magnetischen Agens. $3, 9

53. Alle odpositivon Körper strömen warme, alle odnegativen kalte Odflammen aus (§223). Die Odflammen tragen demnach in Bezug auf scheinbare Temperatur den Charakter ihres Pols, und diese gibt somit einen Ausdruck für die odische Beschaffenheit der zugehörigen Körper. §241

54. In manchen Krankheitszuständen, namentlich bei kataleptischen Anfällen, ist eine eigentümliche Art von Anziehung beobachtet worden, welche die Odpole des Magnets, der Kristalle, der Hände, gegen die krankhaft sensitive Hand ausüben (§23). Sie ist ähnlich der des Magnets gegen Eisen, jedoch ohne Gegenseitigkeit (24, 54), d. h. ohne dass von der sensitiven Hand auch umgekehrt merkbare Anziehung gegen die Odpole ausgeübt würde (23, 91). Selbst durch Leitung und Verladung odisch gemachte Gegenstände brachten teilweise diese auffallende Wirkung hervor. §28

55. Im tierischen Organismus stimmen Nacht, Schlaf und Hunger die odischen Ausflüsse herab; Nahrung, Tageslicht und Tätigkeit steigern und erheben sie (§260, 262). Im Schlafe versetzt sich der Herd der odischen Tätigkeit auf andere Stellen im Nervengebäude (§268). Innerhalb der 24 Stunden des Tages und der Nacht findet eine periodische Fluctuation, ein Ab- und Zunehmen derselben im menschlichen Leibe statt. §265

56. Einige Anwendungen von den durch gegenwärtige Untersuchungen ermittelten odischen Gesetzen sind gemacht worden auf die teilweise Erklärung des sogenannten magneteten Wassers (§27, 28, 73, 105, 112); ferner des Lichtes bei schnellen Kristallisationen (§55); des über Gräbern beobachteten Lichtscheines (§158); des mysteriösen Ereignisses in Pfeffel's Garten bei Colmar (§156); des sogenannten magnetischen Zubers (§135, 151); gewisser Wirkung der Verdauung (§152); der Atmung (§153); mancher sonderbaren Abneigungen der Menschen (§175); der Notwendigkeit, sensitive Kranke im magnetischen Meridiane zu lagern (§69, 71); der Anziehung von Magneten und Händen gegen Kataleptische (§23); des odischen Zustandes des menschlichen Körpers (§79 usw.); der täglichen und stündlichen Zustandsveränderungen desselben (§256); und endlich einiger Eigenschaften und Ursachen des Nordlichtes. §21"

/Reichenbach 1850/ The vital force

Übersetzung der Zusammenfassung, Schluß

CONCLUSION.

IF I collect and compare all the experiments and observations described in the preceding seven treatises, with the deductions made from them, the following propositions, physical and physiological, present themselves.

I. The time-honoured observation, that the magnet has a sensible action an the human organism, is neither a lie, nor an imposture, nor a superstition, as many philosophers now-a-days erroneously suppose and declare it to be, but a well-founded fact, a physico-physiological law of nature, which loudly calls an our attention.

II. It is a tolerably easy thing, and everywhere practicable, to convince ourselves of the accuracy of this statement; for everywhere people may be found, whose sleep is more or less disturbed by the moon, or who suffer from nervous disorders. Almost all of these perceive very distinctly the peculiar action of a magnet, when a pass is made with it from the head downwards. Even more numerous are the healthy and active persona who feel the magnet very vividly; many others feel it less distinctly; many hardly perceive it; and finally, the majority do not perceive it at all. All those who perceive this effect, and who seem to amount to a fourth or even a third of the people in this part of Europe, are here includcd under the general term " Sensitives." § 60.

III. The perceptions of this action group themselves about the senses of touch and of sight; of touch, in the form of sensations of apparent (§ 217) coolness and warmth, ---210--- (§ 225); of sight, in the form of luminous emanations, visible after remaining long in the dark, and flowing frol in the polen and sides of magnets. §§ 8, 9, 15.

IV. The Power of exerting this action not only belongs to steel magnets as produced by art, or to the loadstone, but nature presenta it in an infinite variety of cases. We have first the earth itself, the magnetism of which acts, more or less strongly, on sensitives. § 60 et seq.

V. There is next, the moon, which acts by virtue of the same force on the earth, and, of course, on sensitives. § 118.

VI. We have, further, all crystals, natural and artificial, which act in the line of their axes. §§ 31, 33, 35, 50, 55.

VII. Also heat; § 121.

VIII. Friction; § 127.

IX. Electricity; § 159.

X. Light; § 131.

XI. The solar and stellar rays; §§ 97, 208.

XII. Chemical action especially; §§ 137, 142.

XIII. Organic vital activity; both

a. That of plants, § 248 et seq.; and

b. That of animals, especially of man; § 79.

XIV. Finally, the whole material universe. §§ 174, 213.

XV. The cause of these phenomena is a peculiar force, existing in nature, and embracing the universe, (§§ 213, 214), distinct from all known forces, and here called odyle. § 215.

XVI. It is essentially different from what we have hitherto called magnetism, (§ 42), for it does not attract iron, (§ 37), nor the magnet, (§§ 24, 38). Bodies possessing it do not assume any particular direction from the action of the earth's magnetism, (§ 42), they do not affect the magnetic needle, (§ 38). When suspended they are not affected by the proximity of an electric current, (§ 39); and they induce no current in metallic wires. § 40.

XVII. Although distinct from what has hitherto been called magnetism, this force appears everywhere where magnetism appears. § 43.

XVIII. But, conversely, magnetism by no means appears where odyle is found. This forte has, therefore, an --- 211--- existence independent of magnetism; while magnetism is invariably found combined with odyle. §§ 43, 44.

XIX. The odylic force possesses polarity. It appears with constantly different properties at the opposite poles of magnets. At the northward pole, (§§ 225, 36, note), it generally causes, on the downward pass, a sensation of coolness, (§236), and in the dark a blue and bluish gray light; at the southward pole, on the contrary, a sensation of warmth, and red, reddish yellow and reddish grey light. The former sensation is accompanied by decidedly pleasurable feelings, the latter with discomfort and anxious distress. After magnets, crystals, (§§ 32, 50, 55, 220, 221), and living organised beings, (§§ 84 to 89, 253), exhibit distinct odylic polarity.

XX. In crystals, the odylic poles are found to coincide with the poles of the crystallographic axes, (§ 32). In poly-axal crystals, there are also several axes of unequal force.

XXI. In plants, the caude.x astenden is in general oppositely polar to the caudex descendens; but there are also innumerable subordinate polarities in all the individual organs. § 248 et seq.

XXII. In animals, at least in man, the whole left side is in odylic opposition to the right, (§ 226). The force appears concentrated in poles in the extremities, the hands and fingers, (§ 254), in both feet, (§ 23), stronger in the hands than in the feet. Within these general polarities there are innumerable lesser subordinate special polarities of the individual organs, both in themselves and as opposed to other symmetrical Organs, (§ 254). Men and women are not qualitatively different. § 227.

XXIII. In the terrestrial sphere, the north pole has been considered as magneto-positive, the south as negative; and, consequently, the northward end or pole of the aus-pended needle has been considered negative, the opposite pole positive. On the same principle, I have called the odylic pole which goes along with the northward or negative magnetic pole, negative, that is, odylo-negative, — 0; the opposite pole, odylo-positive, + 0. ---212--- (§ 231). In crystals the cooler pole is, therefore, negative, the warmer positive, (§ 231). In plants, the root was generally odylo-positive, the stein and its points negative, (§ 252). In man, the left side, hand, and fingers were warm, disagreeable, and gave out red light; they were, 'therefore, odylo-positive. The right side, hand, and fingers were cool and pleasant, gave out blue light, and were, therefore, negative, (§§ 226, 231). It is the same, probably, in all animals. § 253.

XXIV. Of the solar rays, the red and those beyond it are odylo-positive; the blue and those beyond it negative. The latter includes the so-called chemical rays. The spectrum is, therefore, polar in relation to odyle. § 116.

XXV. Amorphous bodies, without crystalline direction of their integrant molecules, show, individually, no polarity. But as each of them acta, within certain limits, producing either warmth or coolness, and as they differ in intensity, they form a continuous chain or series, just as they do, electro-chemically considered. Thus the elements, in relation to odyle, arrange themselves so, that at one end there is found the most odylo-positive Body, potassium, at the other, the most odylo-negative, oxygen. And as this natural series coincides almost exactly with the electro-ehemical, we may call it the odylo-chemical series. § 236.

XXVI. The heating of bodies, (§§ 122, 245), and friction, (§§ 129, 246), exhibit 0. Cooling, (§ 123), and fire light, (§§ 131, 244, 266), exhibit — 0. Chemical action gives a result which varies with the nature of the acting bodies, (§§ 139, 142, 147). But in the greater number of cases chemical action developed negative odyle.

XXVII. All stars which shine by reflected light, such as the moon and planets, were, in their chief effects, odylo positive, (§§ 119, 208, 239). Those which shine with their own light, the sun and fixed Stars, were odylo-negative, (§§ 100, 208, 239). Their spectrum was also in itself polar. § 116.

XXVIII. The odylic force is conducted, to distances yet ---213--- unascertained, by all solid and liquid bodies. Not only metals, but glass, resin, silk, water, are perfect conductors for odyle, (§§ 47, 81, 113, 118, 121, 141, 167, 203). Bodies of leas continuous structure also conduct odyle, but not quite so perfectly; such as dry wood, paper, cotton cloth, woollen cloth, and the like. There is also some, although but a small degree of, resistance to the passage of odyle from one body to another. § 47.

XXIX. The conduction of odyle is effected much slower than that of electricity, but much more rapidly than that of heat. The hand, if moved rapidly, can almost follow it in its course through a long wire.

XXX. Bodies may be charged with odyle, or odyle may be transferred from one body to another. In strieter language, a body, in which free odyle is developed, can excite in another body a similar odylic state. §§ 29, 45, 72, 82, 105, 118, 143, 198, 202.

XXXI. This charging or transference is effected by contact. But mere proximity, without contact, is sufficient to produce the charge, although in a feebler degree. § 202.

XXXII. The charging of bodies with odyle requires a certain time, and is not accomplished under several minutes.

XXXIII. Bodies while conducting odyle, or when charged with it, do not exhibit polarity; which seems to be associated with certain molecular arrangements of matter.

XXXIV. The duration of the charge in bodies, after separating from the charging substance, is but short, varying according to the nature of the body, but seldom extending beyond a few minutes for strong healthy sensitives (§§ 82, 167, 169); for the most sensitive patients occasionally lasting for some hours, as in the case of magnetised water. Bodies therefore possess some degree of coercitive power for odyle. §§ 46, 83, 112, 205.

XXXV. Bodies charged with odyle, such as wires, give out at the end furthest from the changing substance sensible emanations, warm or cool, positive or negative, according to the poles from which the charge is taken. §§ 107, 114, 119. ---214---

XXXVI. Odyle has, like heat, the property of existing in two different states; that in which it is sluggish, and is slowly communicated to, and slowly passes through bodies, and that in which it is radiated to a distance, (§§ 193, 254). In this latter form, it is instantly felt by healthy sensitives, without any sensible lapse of time, at the distance of the length of a whole suite of rooms, from magnets, crystals, the human body, (§ 254), and the hands. All bodies and processes, which diffuse odyle over other bodies by slow conduction, radiate it at the same time in all directions, but with varying force; as is seen in friction, electricity, heat, chemical action, and bodies in general, (§ 201). The rays of odyle penetrate through clothes, bed-clothes, boards, walls, (§ 23, note), yet obviously with less facility than magnetism, and with a certain degree of slowness. The conduction and charging of odyle from one body to another, by mere proximity, without contact, as from the polen of magnets and crystals, from the hands, or from amorphous bodies high in the series, such as sulphur, &c. &c. seem all to depend on the radiation of odyle; and this explanation also applies to the so-called magnetising of sensitive persons.

XXXVII. Electric currents, when passed through sensitive persons, produce no perceptible odylic excitement, nor do they directly act on such persons otherwise than on all others (§ 160); but they do so act mediately, and very powerfully, when they excite the odylic state in other bodies (§ 167), which then act on the sensitives. Metals, placed within the sphere of electrical action, produce the most vivid phenomena. § 168.

XXXVIII. The light diffused by odylically excited bodies, is exceedingly feeble, and is, probably on this account, not visible to every eye. Those who am only moderately sensitive must remain a long time, perhaps two hours, in absolute darkness before their eyes am sufficiently prepared to enable them to perceive this light. During the whole of this time, the eye must not be reached by the smallest trace of any other light. But the power of ---215--- perceiving the odylic light cannot depend alone on a peculiar acuteness of vision, because all these who are capable of seeing it, are, without exception, possessed also of that peculiar sensitiveness which enables them to recognise odylic impressions by the sense of feeling, and to distin-guish between the odylic sensations of warmth and coolness, as well as between the pleasurable and offensive feelings they experience; and these sensations are constant. Now, sinne these different powers of perception are, in certain persona, namely, in the sensitive, always present together, we must regard them as associated; and they seem to depend on a peculiar disposition of the whole nervous system, the nature of which is unknown, and not on any peculiar state of individual organs of the senses.

XXXIX. The odylic light of amorphous bodies is a kind of feeble external and internal glow, extending apparently through the whole mass, somewhat similar to phosphor-escence, and possibly depending on a cause common to it and to that phenomenon. This glow is surrounded by a delicate luminous veil, in the form of a fine downy flame, (§ 207). In different bodies this light has different colours, blue, red, yellow, green, purple, but chiefly white and grey. Elementary bodies, especially metals, shine the most vividly (§ 206); compounds, auch as oxides, sulphureta, iodides, carbohydrogens, silicates, salta of all kinds, different varieties of Blass, even the walls of a room; in short, all things give out light. § 206.

XL. Where the light is polar, as in a magnet, (§§ 3, 6), and crystals, (§ 55), it forma a kind of flaming current, proceeding from the polen, and flowing almost in a straight line in the direction of the magnetic or crystalline axes. As it extends further from the pole, it widens a little, and ha intensity diminishes. It exhibits all the colours of the rainbow, (§§ 9, 13), but red predominates in the flame from the positive, blue in that from the negative pole.

Besides this, magnets, crystals, and the hand, like amorphous bodies, possess also, diffused apparently through their mass, the luminous glow, which we may call the ---216--- odylic glow, and this again is on all sides enveloped in a delicate, vaporous, luminous veil. § 8.

XLI. Human beings are thus luminous over nearly the whole surface, but especially on the hands, (§ 92), the palm of the hand, the points of the fingers, (§ 93), the eyes, certain parts of the head, the pit of the stomach, the toes, &c. Flaming emanations stream forth from all the points of the fingers, of relatively great intensity, and in the line of the length of the fingers.

XLII. Electricity, nay even the mere electrical atmosphere, produces, and also intensifies in a high degree, the odylic luminous phenomena, (§ 167), but this effect is not in-stantaneous, occurring after a short interval, not exceed-ing a few minutes. § 169.

XLIII. An electro-magnet exhibits the same luminous ap-pearances as an ordinary magnet, (§ 12), and in the same degree in which it is susceptible of increased mag-netic power, it is also susceptible of increased intensity in the odylic light which it yields.

XLIV. The solar and lunar rays charge with odyle all bodies on which they fall; and if wires, connected with these bodies, extend to a dark chamber, odylic flames appear at their extremity. §§ 114, 119.

XLV. Heat, (§ 125), friction, (§ 129), fire-light, (§ 134, 147, 240), produce at the ends of wires, in a dark place, flames like that of a candle.

XLVI. Every chemical action, even mere solution in water, or the recombination of water of crystallisation in efllo-resced salis, produce the same result at the end of a wire in a still higher degree, (§ 146). But chemical processes also, for themselves, give out odylic flames, and exhibit the odylic glow. § 145.

X LVII. The positive pole yields the smaller but brighter flame, the negative pole a larger but lese luminous one. The former is more bright, because it is red and yellow; the latter less luminous, because it is blue and grey.

XLV III. The odylic flame radiates light which illuminates near objects. This light may be concentrated by a lens ---217---into the focus, (§ 18). The flaming and nebulous ema-nations from bodies and their poles must therefore be carefully distinguished from odylic light in the stritt and proper sense of the term.

XLIX. All these flames may be moved by currents of air, as by blowing on them, when they bend, yield, and divide themselves, (§ 20); when they meet with solid bodies, they bend round these, following and flowing along the surface, just as ordinary flame does. The odylic flame has, therefore, an obviously material (ponderable ?) character.

L. It may be made to flow in any direction, upwards, downwards, or laterally, as the body yielding it is held. It is therefore, up to a certain point, independent of terrestrial magnetism. §§ 20, 53.

LI. The odylo-luminous emanations appear chiefly at edges, corners, and points, (§ 3); and, like electricity, seem to find there an easier egress, coinciding with the resistance to the passalte of odyle observed in conduction. At such planes, therefore, the sensations of warmth, coolness, &c. and the luminous appearances, are especially distinct. § 114.

LII. The flames of the opposite poles of a magnet, &c., show no tendency to unite. There is no perceptible attraction between them, and in this they differ essentially from the emanations of magnetism proper. §§ 3, 9.

LIII. All odylo-positive bodies send forth warm flames, all odylo-negative cold flames (§ 223). The flames, there-fore, in regard to apparent temperature, have the character of the poles from which they proceed, and the flame therefore indicates the character of the body, or pole of a body, from which it flows. § 241.

LIV. In many morbid states, especially in cataleptic fits, a peculiar kind of attraction is observed, exerted by the odylic poles of magnets and crystals, or by the hand, on the hand of the diseased sensitive (§ 23). It resembles that of the magnet for fron, but is not mutual (§§ 24, 54), that is, the sensitive hand exerts no attraction on the ---218--- body by which it is itself attracted (§§ 23, 91). Even bodies charged, by conduction or otherwise, with odyles, produced, to some extent, this surprising effect. § 28.

LV. In the animal economy, night, sleep, and hunger, depress or diminish the odylic influence; taking food, day-light, and the active waking state, increase and intensify it (§§ 260, 262). In sleep, the seat of odylic activity is transferred to other parts of the nervous system (§ 268). In the twenty-four hours of day and night, a periodic fluctuation, a decrease and increase of odylic power, occurs in the human body. § 265.

LVI. Some applications of the laws regulating the odylic phenomena have been made; as the partial explanation of the facts connected with what is called " magnetised" water (§§ 27, 28, 73, 105, 112); of the light attending sudden crystallisation (§ 55); of the lights seen above graves (§ 158); of the mysterious occurrence in PFEFFEL'S garden at Colmar (§ 156); of the so-called " magnetic baquet" (§ 135, 151); of certain effecta of digestion (§ 152); and of respiration (§ 153); of many singular antipathies (§ 175); of the necessity of placing sensitive patients in the plane of the magnetic meridian (§§ 69, 71); of the attraction of the cataleptic hand by magnets, crystals, other hands, &c. (§ 23); of the odylic state of the human body (§ 79 et seq.); of its daily and hourly fluctuations (§ 256); and finally, of some of the properties and the probable causes of the aurora borealis. § 21.

/Reichbach 1849 / Dynamide Band 2

"

Resumee

590

a) das Licht, das der Magnet im Finsteren sichtbar aussendet, von den Sensitiven in verschiedenen Abständen in verschiednenen Farben gesehen wird; jedoch in bestimmter Entfernung für jedes bestimmte Auge die Farbe konstant bleibt.

b) Dies Licht ist in seinen Trägern nicht bloß plastisch vielgespaltig, sondern es nimmt auch in Beziehung auf seine Färbung alle bekannten Formen an.

c) Diese Formen umfassen den ganzen Inhalt des Regenbogens, alle seinen Übergangstinten, und Weiß und Schwarz in allen Abschattungen von Grau.

d) Sie erscheinen dem sensitiven Auge in vielen Fällen einzeln; dann sind sie grau an beiden Polen, oder blau am genNordpol und rot am genSüdpole (original: genNordpol)

e) In den meisten aber, und immer in denen von einiger Intensität, treten mehrere mit einander auf; häufig erscheinen alle beisammen.

f) So wie sie zusammen vorkommen und sich frei ordnen können, lagern sie sich nach der Reihenfolge, welche dem Regenbogen auferlegt ist.

g) Das rote Ende der Iris ist dann unten, das blaue oben.

h) Oben über dem Blau erscheint, vermittelt durch das Zwischenglied des Violett, noch einmal ein reines Rot, so daß das odische Spektrum, das mit Rot beginnt, durch Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau und Veilchenblau hindurch, mit Rot wieder endigt.

i) Diese farbigen Lichterscheinungen bewirken nach gleichen Gesetzen der Stahlmagnetismus, der Elektromagnetismus und der Erdmangetismus (Weltmagnetismus).

k) Der letztere, weil für uns relativ unbeweglich, prägt ihnen gewisse Regeln auf, die für jeden Punkt des Erdballs in der Anwendung veränderte Ergebnisse liefern.

l) Der Erdmagnetismus tut sie in jedem leeren Eisenstabe kund.

m) Die odischen Lichterscheinungen bestehen in allen beobachteten Fällen, und wahrscheinlich immer in einer Iris, ausgenommen vielleicht in eineigen Richtungen, in denen sie grau erscheinen.

n) Innerhalb dieser Iris hat in der Regel eine der Farben, seltener zwei, das Übergewicht in Größe und Intensität. Vielmals wird dann nur diese Herrschfarbe von den Sensitiven wahrgenommen, und die anderen schwächeren entgehen ihnen.

o) Sie tragen in der Regel, wenn sie gegen die Inklination gerichtet werden, graue Farbe; gegen Nord Blau, nach oben Gelb, gegen Süd Rot; dann zeigen sie im Osten Grau und im Westen Gelb. Mischfarben, wie Grün, Orange, Veilchenblau, liegen dazwischen. Dies gilt in den Meridiankreisen, den Horizontalkreisen und den Parallelkreisen mit gleicher Genauigkeit.

p) Treten die Stahlmagnetismen oder Elektromagnetismen durch widersinnige Lage in Konflikt mit dem Erdmagnetismus, so ist die Folge Schwächung und Verfärbung der Odlichtfarben. In rechtsinniger Lage verstärken und beleben sie sich. Zwischenlagen geben vermittelte Abschattungen der Farben.

q) Auch Kristallod, Biod und jeder andere polare Odquell wirkt wie Erdmagnetismus auf anderes Odlicht ein, wenn es damit in Konflikt gebracht wird.

r) Ein Magnetstab, um seinen Achse gedreht, an beiden Enden beflammt, zeigt weder im Vertikalkreise des Meridians, noch in den der Parallele, noch im Horizontalkreise, noch in irgend einer beliebigen Lage an seinen Polen Odflammen, die Komplementärfarben ausmachten, obgleich sie in polarer Opposition stehen.

s) Doch zeigen die Farben des oberen Halbkreises mehr Lichtglanz, als die des unteren. Alle Farben, wenn sie der genNorpol eine Magnetstabes erzeugt, sind glänzender auf derm Halbkreises, der nach Norden gekehrt ist, matter aber auf dem, der nach Süden liegt; die Farben, die der genSüdpol erzeugt, verhalten sich in der Lichtintensität umgekehrt.

t) Die farbigen Odflammen lassen sich vom Magnete auf andere Odleiter übertragen.

u) Magnetstäbe an den Polen in mehrere Spitzen auslaufend, verteilen diese Farben unter ihnen, so daß jede eine ???? dere, ihrer Himmelsgegend entsprechende Farbe trägt, und es läßt sich die Iris jeder Flamme in ihre Elementarfarben zerlegen.

v) Eine viereckige Eisenplatte zeigt auf solche Weise, wie den Magnetismus, so auch das Od, nicht bloß longitudinal, sondern auch nach beiden senkrecht auf einander stehenden Richtungen, transversal.

w) Eine eiserne Kreisfläche, besser noch und vollständiger eine eiserne Kugel, durch welche ein starker Elektromagnet geführt ist, zeigt alle diese Erscheinungen vereint, und besitzt noch eine Anzahl neuer, wodurch sie endlich alle Ähnlichkeit mit der, mit Polarlichtern versehenen Erdkugel gewinnt.

x) Die odische Natur des positiv magnetischen Nordpols der Erde, die odische Natur des Ostens und die des Erdbodens (das Untere) tragen einen gewissen Charakter von Übereinstimmung, in welchem sie dem, welcher den negativ magnetischen Südpol der Erde, den Westen und den allgemeinen Himmel (das Obere) vereinet, oppositionell gegenüber stehen."

Konzentration des Odlichts

"

595

Den Versuch in der ersten Abhandlung §18, in welchem ich bestrebt war, Magnetlicht durch eine große Glaslinse in Gegenwart der Frl. Reichel zu konzentrieren, habe ich seitdem mit vielen Sensitiven wiederholt. Dazu habe ich mit eine große Glaslinse aus Paris verschafft, die bei 0,3 m Durchmesser eine Brennweite von 0,29 m (11 Zoll) besitzt. Dies schwere Glas ließ ich so fassen, daß es in jeder Richtung leicht beweglich war. Ein neunblätteriges großes Hufeisen legte ich in 1 Meter Abstand davon so, daß beide Pole dem Glase zugekehrt waren. Weiter durfte ich mich füglich mit dem Magnete davon nicht entfernen, weil ich sonst zu viel von der ohnehin so geringen Menge Licht verlor; andererseits war die Magnetflamme selbst 25 bis 30 Zentimeter breit, ich durfte also immerhin darauf rechnen, daß ich ungeachtet der Nähe des Lichtquelles eine genügende Quantität paralleler Strahlen auf die Linse erhielt, um sie in einem Hauptbrennpunkte vereinigt bekommen zu können. So vorgerichtet führte ich zu verschiedenen Zeiten die kränklichen Frl. Atzmannsdorfer, Frau Kiesesberger, Frl. Dorfer, Fried. Weidlich und die gefundenen Herren Kotschy und Tirka, den Tischler Klaiber und den blinden Bollmann, auch die Zgfr. Zinkel und Wilh. Glaser in der Dunkelkammer davor hin. Schon der Blinde vermochte drei in verschiedenen Richtungen gelegene Hellen zu unterscheiden, und wenn ich ihn danach tappen ließ, so geriet er mit seinen Händen nach einander auf den Magnet, den er blaßgelblich, dann auf die Glaslinse, die er rötlich und endlich auf den Schild, wo er die Helle weiß, am kleiesten, aber am stärksten angab. Alle anderen Personen erkannten bei einem Abstande der Scheibe von der Linse von 0,3 m bis 0,4 m auf der ersteren einen runden hellen Fleck von 2, 4 bis 8 Zentimeter Durchmesser; die genauesten Beobachter gaben 0,30 m als die Entfernung beider an, bei welcher der Brennpunkt am kleinsten und hellsten ausgebildet erschien; so namentlich Frau Kienesberger, Wilh. Glaser und Jos. Zinkel. Sie sahen dabei alle die Glaslinse rötlich odglühend, also ebenso wie die Glocke der Luftpumpe von den darunter befindlichen Magneten wird, das Licht im Fokus aber weißleuchtend. ---

Herr Kotschy und Frl. Atzmannsdorfer machten mich noch besonders aufmerksam auf einen deutlichen Lichtkegel, den sie, mit der Basis auf der Linse stehend, die Spitze im Fokus sich vereinigen und so durch die Luft leuchten sahen. --- Wenn ich bei Jos. Zinkel und Wilh. Glaser den Schirm etwas weiter von der Linse hinwegrückte oder ihn mehr näherte, so sahen sie den Lichtfleck darauf jedesmal sich vergrößern. Dasselbe gab Frau Kienesberger mit dem Beisatze an, daß jedesmal, wenn ich den Schirm etwas entfernte, in der Ordnung, daß in der Mitte ein dunkelroter Fleck sich bildete, um diesen herum ein gelber Ring sich legte, der zuletzt von außen von einem breiteren blauen Ringe eingefaßt war. Wilh. Glaser, der ich überließ, den Schild im Finstern sich selbst hin und her zu rücken, bis sie ihn am Brennpunkte hatte, sah dabei bald um den gelben Kreis außen herum einen blauen Ring eintreten, bald in seiner Mitte einen blauen Fleck entstehen. Ähnliche Angaben erhielt ich von Jos. Zinkel mehrmal. Es hatte also auch hier eine Iris sich zu entwickeln begonnen. Ich selbst vermochte leider von der Erscheinungn, bei deren Lichtkonzentration ich einige Hoffnungen auf Selbstbeobachtung gebaut hatte, durchaus nichts wahrzunehmen. ---

Der Frau Baronin von Augustin legte ich zwei Magnete über einander, einen Neunblätterer und einen Siebenblätterer, und suchte dadurch den Lichteffekt zu verstärken. Sie sah auf dem Schilde einen runden Lichtfleck von ungefähr 0,15 m (Handlänge) Durchmesser. In der Mitte dieser Helle gewahrte sie eine zweite runde Stelle von 2 bis 3 Zenitmeter (Nußgröße) Durchmesser, die bedeutend stärker erleuchtet war. Dies war offenbar der Brennpunkt der Parallelstrahlen, die auf die Linse fielen. Die Frau Baronin hatte die Güte, auch diese Erscheinung, so wie sie sie sah, in Öl zu malen und damait für Jedermann zur vollen Deutlichkeit zu erheben. --- Genug auf dieselbe Weise, ebenfalls mit zwei über einander liegenen Magneten, führte ich den Versuch mit der Frau Josephine Fenzl durch. Da sie ungefähr von gleicher Stärke sensitiver Reizbarkeit ist wie die Frau Baronin von Augustin, so war es interessant, von ihr ganz dieselben Beschreibungen über Gestalt und Stärke der Lichterscheinungen auf dem Schilde zu empfangen. ---

Um die sensitiven Beschauer zu prüfen, macht ich in der Finstenis verschiedene Abänderungen, die sie weder wahrnehmen, noch verstehen konnten; ich rückte den Schirm vor und rückwärts, zur Seite hin und her, ich schob den Magnet nach rechts und links, drehte die Glaslinse ein wenig auf und ab; in allen diesen Fällen gaben mir die Leute Verschiebungen des Fokus an, wie sie bekannten Gesetzen der Dioptrik entsprechen, und deren Herzählung hier wohl überflüssige Weitwendigkeit wäre. Durch all dies erhielt der früher mitgeteilte Versuch mit der Frl. Reichel durch 4 kranke und 8 gesunde neue Zeugen zehnfacher Bestätigung, und ich kann nur wünschen, daß bald andere gewissenhafte Beobachter sie wiederholen und die gewonnene Tatsachen befestigen möchten *).

*) Beim Schlusse der Verhandlungen der sogenannten Kommission der Wiener Ärzte entstand in ......... "

/Reichenbach 1850/ The Vital force

Vorwort der Englischen Übersetzung

"EDITOR'S PREFACE.

The present publication is the first volume of a work, in which the whole of the observations made, up to this time, by Baron VON REICHENBACH, on the very interesting and important subject on which it treats, are to be permanently placed on record; and, at the request of the Author, I have undertaken to lay these researches, as they shall appear, before the British Public.

The present volume, which includes all that has yet been published in Germany, consists of two Parts.

Part I. is a new and improved edition of that part of the work which was published by the Author in LIEBIG's Annalen, March and May 1845; but no essential alteration has been made in it. It contains a general historical Sketch and summary of the whole investigations, as made up to the latter part of 1844, when it was written; and only entere into such details as appeared necessary to establish the existente of the new Imponderable or Influence, Odyle; and to trace it in the numerous sources from which it is found to flow. These are, magnets, crystals, the human body, the sun, the moon, the starr, heat, electricity, friction, ---Viii---

chemical action, and the whole material universe; and the reader will find various interesting and valuable applications of the facts thus ascertained; for example, to the explanation of corpse-lights, the origin of many ghost-stories, and further on, to dietetics, &c. None of these sources of odyle are, in Part I., treated fully or minutely. The experiments detailed in it were made on upwards of twelve sensitive persons, of whom one half, those who exhibited the highest degree of sensitiveness, were females affected with various diseases of the nervous system, while the remainder were strong healthy men. It is necessary here to mention this, because in various passages, written in 1844, the Author expresses the opinion which he then held, that the sensitive state is essentially a morbid one, and that perfectly healthy persons are perhaps never sensitive. His subsequent researches, as detailed in Part II., have proved the fallacy of this opinion; but the original passages remain, and might, without explanation, puzzle the reader.

Of this First Part, or general summary of the in-vestigations down to the end of 1844, I published an Abstract early in 1846. My object in doing so, was simply to direct the attention of my countrymen to those admirable researches; and to render the work more readable and popular, I condensed the translation into about one-half the bulk of the original, without, however, omitting any essential point. The abridged portions were those consisting of minute and often repeated details of the experiments, essentially necessary, no doubt, to the permanent value of the work, as embracing the evidente produced; but not, in all their details, required for the purpose of directing ---ix--- public attention to the subject; especially as I always intended to translate the complete work when it should appear. I was well aware, and mentioned in the preface to that Abstract, that I was not doing full justice to the Author, in omitting any part of that evidente, but I felt convinced, that in the meantime, a more popular sketch would answer better the intended purpose.

The reception of the Abstract in this country, so much more favourable than that accorded to the original on the Continent, has, I think, fully justified this abridgement. I now present to the public Part I. in its full extent, and in a permanent form; and I am persuaded that, on comparison with the Abstract, it will be found that, in every point but that of the full detail of all the numerous and similar experiments, the summary of Baron VON REICHENBACH was faithfully represented in that publication.

The very favourable manner in which my Abstract has been received in this country, demands my warmest acknowledgements. Not only was the edition very rapidly sold, but I have been, ever since 1846, favoured with letters of enquiry concerning a new edition, and of high approval of the work, so numerous, that I have found it quite impossible to return answers individually to nearly the whole of them. I beg here to apologise for all omissions, and to explain, that I should, long ere this, have republished the Abstract, had I not been in constant expectation of receiving from the Author the succeeding parts of his great work, which I had undertaken to publish in full. The present volume is, then, the commencement of that publication, delayed for reasons which are given ---X--- in the Author's Preface. But I may here state, that the chief of these is not there sufficiently brought into view; namely, the fact, that upwards of three years were devoted by the Author, after publishing the summary in 1845, to a laborious and minute study of all the branches of the subject. The results of these three years' researches, (as far as they concern only one of these branches,) are now given in Part II., which, if published mach sooner, must necessarily have been far less complete than it now is.

It may here be mentioned, that the Abstract of Part I. was favourably noticed in various scientific and literary journals, as well as in the daily press. Indeed, up to this time, I have not become acquainted with any scientific criticisms, published in this country, an the Author's researches, which require any notice from me in this place. This, as will be seen by the Author's Preface, forms a strong and favourable contrast with the reception given to Part I. by various men of science in Germany. It is pleasing to reflect, that a work so truly scientific in its character, has, in spite of the startling nature of the facts recorded in it, received from the British public that respectful and becoming attention, to which, from the known scientific reputation of its Author, it was justly entitled. It must be gratifying to the numerous English readers of the Abstract to know, and to this I can myself testify, that the lamented BERZELIUS took a very deep interest in the investigation, and expressed, in a letter to the Editor, his conviction, that it could not possibly have been in better hands than those of Baron von REICHENBACH.

So much in reference to Part I. ---Xi---